|

|

|

Recorded and edited by |

|

Don C. Wiley

21 October 1944 - 16 November 2001

Don Wiley was the John L. Loeb Professor of Biochemistry and Biophysics at Harvard University until his untimely death on November 16, 2001. Don was in Memphis, Tennessee attending a scientific board meeting at the St. Jude Children's Research Hospital. He was killed when he fell from the bridge spanning the Mississippi River between Tennessee and Arkansas. His death is a great loss to science, but it leaves even a larger gap in the lives of his family and friends. He will be remembered for his contributions to virology (many of which are described here) and to immunology. But those of us who knew him will always remember him for his enthusiasm for science - clearly evident in our discussions - and for his integrity. These were the characteristics most often cited by his students, postdoctoral fellows and colleagues in the many tributes to Don, some of which can be found on the Web.

In my conversations with Don he told me that he probably always knew he was going to be a scientist. He was born in Akron, Ohio but grew up in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, and when he was a kid was a bit of a naturalist, collecting frogs, turtles, snakes, and all those kinds of things but in college what interested him were molecules. He was an undergraduate student at Tufts University where he majored in physics. He remembers, however, that from the beginning he was definitely interested in biology and that a major influence in his decision to become a crystallographer was learning about Watson and Crick - learning about the structure of DNA. In 1999 Don said: "The concept that by learning the structure you get insight into how it works. I think that is exactly what I believed then and what I believe now - not necessarily that you understand how it works, but you get insights into how it works".

Nancy Milburn, a Professor of Cell Biology at Tufts may have been a more immediate influence. Her course in cytology made a big impression on him. He worked in her lab, learned to use the electron microscope and spent several summers working with her as an electron microscopy technician. Don told the following amusing tale:

"For my senior thesis I decided I wanted to take electron diffraction pictures from individual phage heads and I was going to put them in the electron microscope, focus in on them and then take an electron diffraction picture of it (select-area electron diffraction), and solve their structure. I made little crystals of zinc oxide and magnesium oxide. You know this is fun because you take a strip of magnesium and light it with a match. It goes phssssh. You hold a grid underneath it and the powder that falls down, the oxide, sticks on the grid. You put this into the machine and take a look at it by electron diffraction, and you see these beautiful powder patterns. So that's how I got the scope going.

When I put in the phage and took an electron diffraction pattern, I saw spots and almost fainted. But they turned out to be the negative stain crystallizing and it took me a long time to figure that out. Interestingly at that same time, Aaron Klug was doing the right thing. Namely, he was taking electron micrographs of the phage head and shining a laser through the micrograph negative and getting the optical diffraction pattern. So he was getting a diffraction pattern of the phage. I didn't know enough diffraction theory to even know why what I was doing wouldn't work. That was a problem. I was too much of an empiricist at the time. I learned later that it's better to know what you are doing."

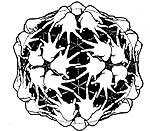

A third and major influence was Don Caspar. In 1964 or '65 Don heard Caspar give a seminar at the BioLabs at Harvard. Caspar and Klug had recently developed their theory of quasi-equivalence. Don remembered that "Caspar showed all these spectacular drawings that he had including a drawing of a virus T=7 lattice with the repeating unit being a human hand. The point was to show that you could have a right or left handed lattice, made from all right hands. It was 'inspirational'". It was the first step in convincing Don to become an X-ray crystallographer.

| Don Caspar's drawing - 60 identical left-handed enantiomorphic structure units. (reprinted from Biophysical Journal v.32, page 104, 1980, with permission). |  |

Don Caspar was also one of the major reasons Don Wiley chose to go to graduate school at Harvard. Caspar was a Professor at the Harvard Medical School. His lab was at the Jimmy Fund next to the Children's Hospital in Boston. Here is Don's recollection of his first visit to that lab:

"It was just fascinating to go and see because Don had a room outside his office - ostensibly the library but it was mostly filled with molecular models that he had made of viruses and various things illustrating different features of quasiequivalence. And who should be sitting at the Nikon comparator but Steve Harrison, whom I had never met, looking at X-ray pictures of bushy stunt virus crystals on the microcomparator. The microcomparator is something that projects the film up onto a big screen in front of your face and then on that screen he had a little strip of film of X-ray exposures that he had taken for 1 second, 2 seconds and 5 seconds and 10 seconds, etc. He was comparing the dots on the X-ray picture with this calibrated strip, measuring by hand the intensity of the diffraction pattern and writing down in a little list h, k, l, intensity. Now it's all done automatically. I tell you that this was absolutely astounding to me. I had never seen any of the mechanics of crystallography up until that time. I thought it was done only on small proteins, and here they were doing a whole virus."

Don worked in Caspar's lab in the summer before and during the first year of graduate school. Both Dons became interested in allosteric enzymes, in the conformational changes they undergo and eventually in the enzyme aspartate transcarbamylase, a protein also of interest to Professor William Lipscomb in the Chemistry Department at Harvard. Don Wiley ended up working in Lipscomb's lab where he helped determine the structure of aspartate transcarbamylase.

Lipscomb had studied with Linus Pauling. Before coming to Harvard he had been in Minnesota where Michael Rossmann had been in his lab from 1956 to 1958. Lipscomb carried on research in three areas simultaneously: theoretical studies on chemical bonding, Boron chemistry and Boron hydride structures, and macromolecular crystallography. He received the Nobel Prize for work on Boron chemistry. In addition to his scientific achievements, he played the clarinet with the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra and found time to be a competitive tennis player. Lipscomb was one of the early crystallographers to work on proteins and his group determined the structure of carboxypeptidase about the time Don joined the lab.

But Don Caspar continued to be a source of ideas and enthusiasm and Don Wiley recalled:

"Don (Caspar) has a pure view of science . He is not an empire builder or a person striving after prizes or someone driven by ego and so on. He is just an immensely curious person with a kind of strangely mechanically oriented and mathematically oriented mind. Don knows, I think, really that he is the inspiration for a lot of people. Don turns out to have people all around who look up to him as the archetypical person or scientist who really delves into structural things."

Aspartate transcarbamylase was the largest protein to be solved at that time. It has a molecular weight of 300,000 roughly 10 times larger than the other proteins, lysozyme, myoglobin, carboxypeptidase and RNAse, whose structures had been or were being determined. Those were in the 30,000 mol wt range. This was 1967 and there had not yet been a high resolution structure of hemoglobin. Don Wiley said that he spent most of his graduate school career writing software to make it possible to scan films so you could collect data by film. He remembers being motivated by the idea that he would work on film scanning which would then make it possible to collect data on much larger things. He said:

"I was very nuts and bolts inclined. I liked taking things apart, actually making the X-ray camera, actually collecting the data, actually writing the computer programs".

In 1971 Don Wiley received his Ph.D. in Biophysics from Harvard University and was offered a position as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. This is where our detailed oral history begins.

SS When you were offered an Assistant Professor- didn't you have to write a grant?

DW Not for a little while because I just stayed right in Lipscomb's lab and continued doing what I was doing - which was trying to figure out how to make oscillation photography work well (something which was also going on at the MRC at the time). In the beginning, I did write a grant which was not funded. Not only was it not funded, but in those days the scale went from 1 to 5 or the grant could simply be disqualified - they could just say NO. That is what I got for my first grant.

SS It would be wonderful if you had that letter.

DW I would just as soon not find it. It's probably around. I tend not to throw things away. But they were right. The proposal was more or less nonsense. At the beginning I was going to try to work on protein-DNA complexes. But I had no interest in it, so I really floundered around for about 3 years or so and really didn't do anything. I learned to make CAP protein and show its binding to DNA, I planned to make crystals.

SS Did you move out of the Lipscomb lab?

DW I moved down to the first floor of Gibbs Laboratory into my own space (that I shared with Steve Harrison) but I really didn't accomplish anything. And in fact, I had no real motivation. I often say to students that the most important thing is that you have an inner desire to work on what you are working on, so that you get up in the morning excited about going and doing it! Well, I know that from past experience of having had the opposite feeling during that time.

SS It must have been very discouraging for you.

DW Yes - it was extremely discouraging. In fact, I thought of leaving science many times. Eventually, it was actually Don Caspar who saved me when I was losing motivation to do science, because I wasn't finding things that were interesting. Don put together a program project with Alice Huang to study viruses. Steve had already taken some X-ray pictures of Sindbis and some enveloped phage.

SS PM2.

DW That's right, that had membranes, and Steve had shown that you could see the transform of the membrane in the X-ray scattering of viral pellets. He had written a little paper on that subject (Harrison, SC, Caspar, DLD, Camerini-Otero, D and Franklin, RM Lipid and Protein Arrangement in Bacteriophage PM2. Nature New Biol. 229:197, 1971). Don Caspar had me get together with Alice (Huang) and a few others. So, I picked up some VSV and did the same thing. I have still never published it. What was fun is that VSV is cylindrically symmetric instead of spherically symmetric, so that I got to use Bessel functions. I thought it was great. It was really fun, but it didn't come to much. I just thought that somehow that research would lead the way to working on membranes, which I had started in Don's lab but stopped.

Viruses are just interesting to me - inherently interesting, I would claim. Now there are other people who say that about protein-DNA interactions. I am not one of them. And so Don brought me in by getting me a budget on a program project to start working on VSV. My first independent idea on the subject was to try to get a crystal structure of VSV G - the glycoprotein. In the literature it said that the glycoprotein was shed into solution as a so-called 6S antigen. Alice Huang was making tons of VSV all the time and so she agreed to save the supernatants after she had spun out the virus. I hired a technician and began stockpiling supernatant in the refrigerator. I had gallons and gallons of this stuff from which I was going to isolate the 6S and crystallize it. But such was my ability at the time that I never even isolated 1 mg of the stuff. But somewhere along the line, I woke back up and I got interested in what I was doing in a serious way and starting casting around to see if there was something even more interesting. I mean VSV was interesting because of defective interfering particles and rabies would have been interesting. But I seemed to need something to catch my attention, and flu caught my attention. I then started learning about the lore of influenza virus.

SS How did you learn about this?

DW Steve and I gave a course and Alice (Huang) gave a course immediately after it. So, I sat in on her course in virology and I began reading more widely also.

SS This must have been in the early 70's.

DW Yes - I think my assistant professorship started in 71. So sometime in the early 70's Steve and I started teaching a course together which was on structure. It was much more eclectic than we tend to do now - bacteriophage, assembly pathways. quasiequivalence - all kinds of neat things. Anyway I don't know exactly where it was that I discovered that John Skehel had cleaved the hemagglutinin off the surface of influenza virus. By this time I knew a bit of virology, especially the kind of virology that was being done in those days: Here's the name of a virus and here's what the SDS gel looks like and if you nibble on it with proteases, these are the things that must be on the outside because they disappear. Lots of papers were like that at the time. I was looking at them all, looking at the proteins on the outside - thinking about them, thinking about how the virus could get into the cell.

SS Did your interest in the ones on the outside come from your interest in membranes?

DW Yes, that's right- absolutely. I was interested in membrane proteins and at that time - although it seems crazy now since you can isolate membrane proteins easily - if you had purified a virus, you already had purified a membrane protein more than you could purify membrane proteins at the time. So a pure virus represented the first huge step toward a pure membrane protein. My plan was to work on membrane proteins that way, but we ended up chopping it off the surface and not doing the membrane part for years and years although we may have a crystal of that now. (More of this - later)

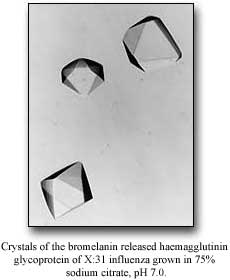

John had a student named Colin Brand who had worked with him and tried every protease and unlike all the other people in the field at the time - and this may be an overstatement - who were just finding out: what's on the outside, what's on the inside, what's susceptible and so on. John was more of a biochemist and so he actually looked to see what came off - not only that it disappeared. He found that with bromelain, the hemagglutinin came off essentially intact. It lost 10 amino acids in the linker and the transmembrane anchor that goes into the membrane. The whole rest of the molecule came off intact. He characterized it in various ways, publishing in the paper in Nature that there were small crystals. (Brand, CM and Skehel, JJ Nature New Biology 238: 145-147, 1972) So I got in touch with John.

Now in retrospect, it turns our that those were probably the neuraminidase crystals because the neuraminidase crystallizes extremely easily and they had a morphology of neuraminidase crystals. But what's important is that it seemed possible to me that we could crystallize it.

SS You didn't know him at that time?

DW No, I didn't know him but I didn't know many people. I got in touch with him by mail and asked him whether I could try it out. I said that I was going to make some HA myself and I got the X31 strain of virus from Ed Kilbourne. I started growing virus in embryonated chicken eggs, not having a clue of what I was really doing. John was, meanwhile, doing 5000 eggs a week. So John sent me a small sample of the HA and I got crystals almost immediately.

DW No - he sent me a small sample of the hemagglutinin and I got crystals

almost immediately after a funny thing that happened on the first day when I

was concentrating some stuff and looked in bottom of the concentrating vessel

and saw this thing shining back at me- it turned out to be a piece of glass

- but I remember jumping up and down. I can't actually recall how much longer

after that, I saw my first crystals, but I did see a crystal pretty soon. The

first real crystals turned out to be no good - it was a crystal that

looked like a pentagonal dodecahedron, but it was really a million tiny crystals

all in a mass, looking like one crystal.

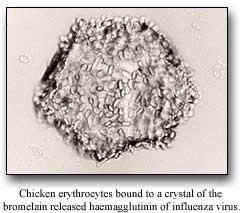

But shortly after that, I did what I consider the "coolest experiment" that I had ever done, which is I added red blood cells to the crystal and they stuck and that's the proof that the hemagglutinin was still capable of binding to the sialic acid on the surface of the red blood cells. And I never published it either - and never did the controls - ah the controls are hard.

DW Then I met John. He visited the lab one day for a couple of hours with Mike Waterfield. It was not very eventful, but we got along. Probably everybody gets along with John. Later we became good friends. I then went that summer to the Madrid virology meeting (1975) and that's where I discussed a sabbatical with John. I made plans to go on sabbatical to his lab. But by the time I was on sabbatical in his lab, we already had crystals here and were trying to collect data.

SS Was there anyone working with you in your lab?

DW Almost no one - I was trying to do everything myself, with a technician, and my first graduate student, Judy White, helped break me out of that. To give you some further idea of our naive - by that time we had a clear idea of what we wanted to do. We wanted to determine the structure of the hemagglutinin because it would be shown in the future that it would do membrane fusion. It hadn't quite been shown at that time, but there was the obvious analogy with the fusion protein of Sendai which was cleaved for Sendai fusion and that protein was known to be involved in fusion as the result of work by (Purnell) Choppin. Then Judy White was going to work on Sendai virus so she would do all the functional stuff and I would do the structural stuff. Five years later - it would be wrapped up. You can obviously measure all the fusion things that you could ever want to know by using Sendai and we didn't yet know how to make flu fuse. That didn't happen until low pH was discovered. So that was the plan. In the end, it obviously didn't work out that way. And then Ian Wilson joined me as a crystallographic post-doctoral fellow.

SS That was after you were on sabbatical or before?

DW That was after. While I was on sabbatical Carl Pabo was actually left working in my lab as a rotation student and he was collecting a little bit of data on hemagglutinin and then he got interested - and always was - in protein-DNA interactions. He then worked with Bob Sauer. Sauer was a student with Ptashne. He (Pabo) worked with Sauer and they did Lambda repressor. But when I came back from sabbatical or shortly after that, I think, Ian (Wilson) came and Ian and I worked together on HA - we very much worked on it hand in hand.

SS I'm sure you would like to tell me a little bit about your sabbatical. Where did you live?

DW In Edgeware because it was near Mill Hill and I was also going up to Cambridge to use an X-ray camera that Richard Henderson and Nigel Unwin had just used to show that the helices in bacterial rhodopsin must be perpendicular to the membrane. They had done that by aligning molecules and taking X-ray patterns and seeing the diffraction from the helices and in which direction those were relative to the membrane. And I wanted to do that with the transmembrane helix of glycophorin because you could easily get that helix as a result of purification worked out at Yale by (Vincent) Marchesi. The peptide was called TIS and I made a bunch of that peptide and actually had some help from Mark Bretscher because I was trying to do labeling experiments on it. Mark had this nifty labeling thing he was doing back in those days on membrane proteins. And so I was trying to pack enough of that transmembrane anchor into liposomes and then pack the liposomes into a capillary and get an X-ray pattern to show that they were in fact helices and perpendicular to the membrane. That it was ever a question seems so crazy now. At the time the general view of how the hemagglutinin was in the virus did not include a trans-membrane component.

As I recall it, there wasn't anybody at the time that I found who actually

believed there were transmembrane tails in there except probably Ari Helenius

and Kai Simons. They were at that time taking things apart in detergent and

so on and I was very tuned in to what they were doing. When I went on sabbatical

in John's lab there was no chance in the early stages of getting the transmembrane

part of hemagglutinin. That was too difficult. So the idea was I would get the

transmembrane part of glycophorin and the rest of hemagglutinin and put them

together. "Look, this is a helix and this is how it all goes." I never

really got that to work. I never got the scattering experiment to work well.

Always had trouble making enough of the peptide and my heart wasn't deeply in

it. I was more intent on doing studies that I was doing in John's lab trying

to prove that the HA molecule was a trimer by chemical crosslinking. It was

critical to know that in order to use the non-crystallographic symmetry to help

solve the structure. And if you had to worry about is it a dimer or trimer or

tetramer, that's too many options, and you had to know. There was every reason

to believe at the time - for reasons I can't remember - that it was going to

be a trimer.

SS At that time- did you have X-ray diffraction patterns of hemagglutinin?

DW Yes, before I went over, there were diffraction patterns from a second crystal form (and points to a picture of it and says) those are the pictures up there.

Those photos are the actual ones from my poster from the Madrid meeting and I remember people coming around at that meeting and saying: "Oh my god" - because in virology in those days - the idea that you would take some protein that all these people had been working on for so long, and actually crystallize it - they could see the change coming, if you know what I mean. I remember Laver and Webster and people like them who I didn't know at the time - they came around saying: "what is going on here".

I guess I was only on sabbatical at Mill Hill for about 9 months. They were some of the most productive months of my life. One of the reasons was that when you went to John's lab - John didn't have an office - he literally had a desk in a room that was filled with electrophoresis apparatus. I was accustomed to an office by this time in my life, half a secretary and all this. And I said where should I sit? And he said: "Well, let me see" and he pushed a few things out of the way in the lab and gave me a stool.

John's lab was so crowded that I never had a desk. I had a stool like a bar stool and a patch of bench that I called my own, which was about 2 feet. Most of the people had nothing, everybody used the space and just ran around. And in that respect John is quite a scientist to watch. He's a bit like an orchestra conductor. He'll stand in one place and the technicians are running and getting things for him and he's pouring things together and he's saying "go get the centrifuge". But at the end of a few hours he's accomplished a lot because it is like he has 6 hands – people are running around doing things. It was a very good experience.

And we became friends and we also learned the elements of each other's science from each other so we didn't have to take it on faith - so to speak. Also we learned how to tell the other person the news that it was really like this and not like they thought and still be able to get along afterwards. Neither one of us is inherently very flexible but on the other hand we have an arrangement where we never had any problem getting information back and forth from each other even when it contradicts our preconception which in those days was important because the structure people and the biochemists were pretty far apart in terms of how they imagined things being. This whole business of whether there would be a transmembrane helix and whether the outside part would be independent of the part in the membrane and things like this. A structure person would have very strong opinions about that based on their feelings for how proteins must be from the few examples at the time whereas people in virology and biochemistry – they were operating in a different way at that time

SS It goes back to what you were saying at the very beginning that you had to understand about molecules.

DW Absolutely, I must say - to me - what I really liked about flu was the fact that there was a lot of phenomenology- periodic epidemics with the same people being reinfected - occasional pandemics, world wide epidemics, of the sort that were obviously different and that had a different virus. By that time reassortment had been shown. The idea that viruses like flu must be getting into the cell - and that viruses like Sendai caused fusion. I think it was logically accepted by many people that the other viruses were doing fusion as well. It was just a question of how that was going to be shown and eventually understood. To me it was interesting because it was something cell biological (as opposed to moving electrons around in an active site) - like vesicle fusion at synapses or sperm with egg or all the kinds of Golgi fusion and so on.

SS Most of that wasn't known at the time.

DW Well, you knew about parts, you knew there were synaptic vesicles. I learned that in cytology. I always saw these Golgi stacks and everything and it was clear that there was secretion from these stacks - the idea that they might have connected directly was certainly around and still is. Certainly the (Jim) Rothman sort of vesicles weren't known. But the idea that there were vesicles, that there were fusion events of all sorts, and that the viruses were doing those – that was clear. And the idea of receptor binding. In my mind at the time - any ligand binding any receptor was conflated with the virus binding to the cell surface. So, at the time- I thought "we'll work on the virus and just have all of these things right in one little package".

Another thing is that viruses - there are always little stories associated with them. They are infectious. It's like having your favorite organism. Well a virus is like that. Some people like snakes, some people like frogs. It's very easy to like viruses because they do things. You can be fascinated by what they do. And I think that's the part that I got in a way from Don (Caspar) from the beginning with the idea that the viruses being complex and being able to do things.

SS But you must have gotten from John the whole lore of influenza.

DW The same sort of thing that I had picked up a bit from sitting in on Alice's course. All the different viruses and how they do all kinds of different things. Then I got to know John. John at the time was the head of the World Health Organization Influenza Center in London so all the strains from around the world were coming in and during the time I was there - that was the time of the swine flu scare in the U.S. So I heard all about that first hand from John who was right on the front lines of the whole thing. Visit Skehel Oral History . So it was really fun. I really liked that and I still do. The other thing I work on - immunology - is somewhat the same way. You have multiple sclerosis, insulin dependent diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondelitis. In the work that I've done I have touched peripherally on the molecules that are involved with these and it is the interest in the bigger subject that makes me want to look into the little subject to see whether there is any relevance. Unfortunately, sometimes there really isn't; that I can see anyway.

SS. You can still learn something about the molecule.

DW That's right. In a way, for me, the molecules are almost like an entry point into a more complex subject, whereas I would find it difficult to enter those subjects from another point of view. But pick out a single molecule that would be interesting as a way to get into the subject - to get interested in it. Therefore, read about all the other aspects even though you are only working on this aspect. I think that's something about being a scientist. It is that you enjoy everyone else's science as much as your own, really. You go to seminars not to hear what people are doing in your own field. In fact, when it is in your own field your response is complicated because either it isn't quite how you thought it was going to be or you thought you should have done it or that guy isn't good or all these kinds of thoughts. Whereas the whole enterprise of science is really interesting especially if the enterprise happens to impinge on the things you are interested in. So for example in something like flu - people get sick in Hong Kong - you suddenly think boy that's just what I'm interested in.

SS So now let's go back - in England you were doing a lot of biochemistry and you started talking about the hemagglutinin being a trimer and how important that was.

DW What we were really doing was following a paper by Davies and Stark where they had used a chemical cross-linking reagent called dimethyl suberimidate and we were chemically crosslinking the hemagglutinin under all sorts of conditions: on the surface of the virus, on the surface of the cells where it was budding out, in detergent micelles, after it had been cleaved with bromelain, and showing that in every case it was still a trimer. That was important, obviously we had to know what it was for the noncrystallographic symmetry. We had to know that we were really looking at the real thing and that it hadn't fallen apart in some way or something. It's amazing how many gels you can run to establish one point. Nowadays I expect a student to come up with an answer to that in one or two gels. I would guess that I ran gels for 6 months before coming to the firm conclusion and then we wrote a small paper (Wiley, DC, Skehel, JJ and Waterfield, M, Evidence from studies with a cross-linking reagent that the hemagglutinin of influenza virus is a trimer, Virology 79: 446-448, 1977).

That was during the time that Waterfield was trying to sequence the hemagglutinin. Waterfield and Skehel were sequencing and Judy White - because I had left the lab here (at Harvard) she went on "sabbatical" to be in Waterfield's lab and worked with Mary Jane Gething and Waterfield and they sequenced the fusion peptide from Sendai. Skehel and Waterfield had earlier sequenced the N-terminus of the Flu HA, now known as the fusion peptide. The point is that when you saw that they both had similar sequences - that settled it, because the Sendai fusion protein by that time was known to have to be cleaved. Klenk and Choppin had shown that it had to be cleaved in order to get fusion. Sendai had to be cleaved. It was later shown that the hemagglutinin had to be cleaved to cause fusion. If you looked at the 2nd polypeptide chain, namely the new N-terminus, they were essentially homologous sequences - non polar amino acids with glycines about every 4 residues. So the vague idea that Judy and I had that these molecules were really doing the same thing was clearly made likely by that observation.

SS. But at that time, fusion with hemagglutinin hadn't been shown.

DW Hadn't been demonstrated. Right, except you knew the virus was getting into

cells so there must be fusion. You just didn't know how the virus did it. The way I

thought of it at the time was that Sendai had an overzealous fusion protein that when it

got into cells, it just couldn't help itself and fused everything together. But the fact

was that Sendai could fuse on the cell surface and flu had to get inside endosomes to fuse

which it did by low pH. That hadn't been established and the idea that there was low pH

wasn't known then. When the structure was published in 81 - sometime shortly after that

these experiments by the Japanese actually showed that the virus could cause fusion if you

lowered the pH (Maeda, T and Ohnishi, S, FEBS Lett. 122: 283-287, 1980). John would

undoubtedly know that history well.

We're skipping over for the moment the structure but we'll get back to that. In 1982, John made what I think is THE discovery. He doesn't agree, he thinks that it was the structure. He's the person who lowered the pH of some hemagglutinin and showed that the hemagglutinin underwent a conformational change that was clearly the equivalent of fusion in the sense that you took BHA which was not a membrane protein, lowered the pH to the pH of the endosomes and it became a membrane protein. If you did it in the presence of lipid vesicles, it stuck to the lipid vesicles without a transmembrane tail, or if you did it in the presence of detergent micelles it stuck to detergent micelles, or if you did it in the presence of nothing - water - it formed rosettes which you could see in the electron microscope and looked just like the hemagglutinin would look with its transmembrane tail before you lowered the pH. It looked like a membrane protein in water; namely, a protein-protein micelle so that really established I think the important thing.

SS Do you think it established it at the time?

DW The paper was clear about it. Whether anyone else got it is another issue. We got it - believe me. I remember that one of the things we were worried about is - well, maybe the protein is just completely falling apart and we would talk everyday over the phone and I think it was me who had the 'brilliant' idea of asking whether it hemagglutinated after you lowered the pH. Because before you lowered the pH, BHA won't hemagglutinate because it's not rosettes but after you lowered the pH if it really stuck together as rosettes and it were really still the hemagglutinin and hadn't been shot in some way, then the binding sites should still be O.K. and it should hemagglutinate. Sure enough it did. So then we sort of knew that the molecule was undergoing a conformational change. It hadn't lost its ability to bind its receptors so that meant it had to be mostly folded but it had gained the ability to stick into lipid vesicles or into detergent micelles. If it can stick into a detergent micelle or into a liposome it's a membrane protein - which was really as a result of the work of Kai (Simons) and Ari (Helenius) and others - the definition of a membrane protein. So a non-membrane protein had been converted to a membrane protein by lowering the pH. What more could you want? That is how you are going to get a fusion peptide into the cell's membrane. We explicitly stated it in that paper. I would have to look back to be sure, it was a PNAS paper (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79: 968-972, 1982). That it would stick into the cell's membrane - clearly we thought that.

At the time John took it to some person and said "should we patent this?" We basically discovered that this protein had to change dramatically and we thought maybe you could make antibodies against the changed state. That was one of our ideas, but I don't think that ever got written down. We would make antibodies against the changed state, because normally induced antibodies don't cross react from one epidemic to the next maybe they would cross react in the changed conformational state because there would be all this hidden stuff that it has to use - all this machinery that had to be conserved that would all be visible. The antibodies against that - you can't change that part of the structure and you won't get antigenic variation. Of course the antibodies would have to get into the endosome to work and so on. I asked John recently whether we had ever actually done those experiments because we had considered it. I know antibodies were actually made against it but did they ever block infectivity? Obviously they didn't or we would have published it, I guess. But anyway we went through Harvard. I can't remember exactly why and they considered patenting it and then a few months later we got this note back – No! They looked around the companies and nobody thought that it was interesting. Maybe if we had been smart enough to say all viruses would do this, it would have made a difference. I think we would have said it for any virus which was known to have its glycoprotein cleaved. If the glycoprotein has to be cleaved then it is in the formal class of the hemagglutinin. But who cares. I can literally say that with absolutely strong feeling.

SS One can say that about the reverse transcriptase which didn't get patented

DW No I read about that (in an oral history that SS did with David Baltimore). But those were different days and when we were thinking of patenting it, we weren't thinking of getting rich or starting a company. We were just thinking that - well, that's what you do when you've made a real discovery. We hadn't made any real discoveries. John may have but I certainly hadn't made any real discoveries before that.

Continue to Pt.2 of Oral History |

| Introduction

| Some historical highlights: structural virology

and virology |

| Solving the Structure of Icosahedral Plant Viruses

| Picornavirus Structure | Poliovirus

| Polio

The Influenza Virus Hemagglutinin | The

Influenza Virus Neuraminidase

| Issues of Science and Society |

contributors| Home |

|